History of football stadiums

Sport activities elicit fervent responses from people and the passion of players matches the excitement of spectators and fans. The global sporting industry is worth over $600 billion and with the amount of money circulating, major sport arenas boast impressive structures. Speaking of architecture some are more remarkable than others. But, how did football stadiums look originally? How did they evolve? Who are the individuals who changed the pitches from the set aside grass areas to properly maintained stadiums?

The first stadiums

When Association Football was in its starting phase, people played their matches on spare playing fields, mostly within the public parks. The biggest worry of players was whether passers would understand exactly what was happening and have the courage to walk around the pitch.

With growth of football popularity and professionalism, the need to develop better grounds where players would like to be arose. Football clubs started doing more than just brushing some debris off the grass and sending boys out for short matches. Ground that could be used for football and other games, like rugby, had existed for a while. The very first ground, Sandygate Road, opened already in 1804. Almost 60 years later, the first football match between Hallam and Sheffield FC was played here.

Initially, the markings seen on the local pitches were non-existent. Football pitches featured bollard or fence along the field edges to help players know where they could not go beyond and to keep the spectators closer. In addition to that, the fields featured two sticks, fundamentally, at each pitch end to represent the goals.

It might seem strange to hear that football pitches were the suitable looking grassy areas. In most cases, it was the ideal section of the public park – the straightest part. As the popularity of this game increased, teams started using private land. For example, Preston North End moved in 1875 to Deepdale to play its matches on a ground that was formerly a farm, and considering the initial state of the field, they encountered numerous problems.

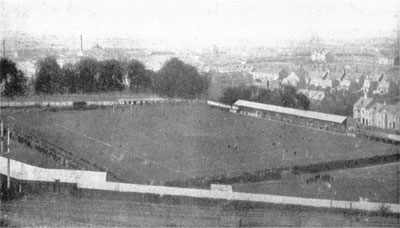

Dunstable Road, the home for Luton Town FC 1897-1905.

The period 1889-1910 marked a start of an era of numerous stadium constructions in England; fifty league clubs moved to new stadiums during this period. The stadiums were commonly built in centrum city areas - a circumstance that have created difficulties when the need for an expansion has arose much later.

The stadiums were relatively alike from an architectural aspect. They featured one or two covered grandstand and open terraces was filling out the rest of the oval form around the field.

The overcrowded stands in the late 19th centuries were a proof of the increased interest for the sport in England. In the early 20th century, enormous crowds were gathered in special occasions as finals in competitions. One such occasion was the 1913 FA Cup final played at Crystal Palace with over 120,000 spectators. The overcrowded stands would lead to the first recorded stadium disaster, which happened in 1902 when parts of a stand at Ibrox Park in Glasgow collapsed. The outcome was 25 killed and more than 500 injured. Football historian David Goldblatt writes in The Ball is Round: "The Ibrox disaster was driven by combination of enormous crowds, and a commercialism that sanctioned under-investment in shoddy infrastructure."

Development of football stadiums

Before 1960, football pitches featured regular grass. Later in the 1980s, developers installed drainage systems in them. Originally, pitches required substantial amount of maintenance to keep them in the right shape. They were reliant on regular lighting and watering.

In the year 1958, people witnessed undersoil heating put underneath the football-playing surface in Goodison Park. The twenty miles – roughly thirty kilometers – wire was laid under the surface, costing the football club over £16,000. The purpose of this heating system was to prevent freezing on the pitch and was more effective than the installers thought. And because the ancient drainage system could not cope with the new water floods, the pitch was taken up and relaid in 1960 and better drainage systems installed.

Still, in the year 1960, people witnessed the introduction of first-generation artificial turf. The first-generation artificial turf was very different from the pleasant lifelike artificial grass on soccer pitches today. It was low-piles, stiff nylon fibers attached to asphalt or concrete bases. It was first installed in Astrodome Texas. Professional footballers encountered artificial turf when Luton Town, Queens Park Rangers, Oldham Athletic and Preston North End introduced the second-generation turf to their fields in the year 1980. The United Kingdom government illegalized artificial turf in the year 1995.

The game is on at the Meadow Lane in 1981.

The modern football stadiums

In the year 2001, UEFA and FIFA started quality assurance programs for artificial turf development. That helped them come up with industry standards for its use in the soccer world. And as a result, the International Football Association Board tackled the problem of turf in the 2004 Laws of The Game.

4G pitches, also known as fourth generation pitches, came into being in the year 2010 and their popularity has been growing. The pitches are a hybrid of natural grass and artificial turf and people can therefore use them for a very long time without any sign of wear and tear. The increased popularity of turf results from the improved image of The John Smith’s Stadium in Huddersfield.

Deesso Grassmaster pitches are now common in our stadiums, but were laid for the first time in 1996 in the home of Huddersfield Giants Rugby League Club and Huddersfield Town Football Club. The benefits of artificial and real turf hybrid are clear. Maintenance problems that were common in earlier days are no longer a big problem. Football pitches are not lit or watered regularly and groundskeepers can easily monitor them.

Camp Nou by night.

Football arenas such as Camp Nou in Barcelona, gives the sport events another dimension by their grandiose and spectacular framing.

The stadiums have grown bigger and bigger, but on the same time the maximum attendances have decreased. The shift from standing places to seats has increase the safety a lot, but it also means that some old records, such as the 173,850 (unofficially, the attendance has been estimated to be over 200,000), at the Maracanã stadium the 16 July when Brazil played against Uruguay in 1950 World Cup will probably never be broken.

The shift to all-seater stadiums was a result of the Hillsborough disaster in 1989. A regulation stipulated that standing places should be removed completely on all Premier League venues before the start of the 1994-95 season. The same rules have been introduced in several other countries. FIFA and UEFA command nowadays all-seater stadiums for all their competitions.

Typical interior design with rowes with seats in levels at Wembley Stadium.

The economic impact of stadium capacity

The size of a football club's stadiums also reflects the revenues. A team with 30,000 capacity has a major handicap against a team with 60,000 capacity. The latter team can afford bigger players transfers and player wages. In Premier League, Manchester United's Old Trafford was for a long time superior to Arsenal's Highbury in this aspect. Arsenal though the disadvantage was enough critical to invest almost £400 million in a new stadium, which was the Emirates stadium that was ready in 2006. The same route was chosen by Tottenham. White Heart Lane had been their home for over a century, but the revenues from its 36,284 capacity couldn't match that of the other English top clubs. The solution was a gigantic investment that resulted in a plus 60,000 capacity stadium with a removable turf field.

A third factor, besides the amounts of fans that can be capsuled and the revenue aspects, is the symbolic and commercial value. A stadium is an important symbol for the team and when a new stadium is built it should look impressive. In many ways … as Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg puts it in The Club: "Arsenal's new stadium wouldn't just be a venue for 60,000 fans attending in person, it would be a backdrop for the 60 million watching around the world".

Tottenham Hotspur Stadium is hard to miss if you are in the neighborhood.

Football stadiums gets enormous media exposure, which has opened win-win situations for owners and other companies. Several clubs have profited by given naming rights to companies that is willing to pay for the branding opportunity. Some examples are Allianz Arena (Allianz is a financial services company), Bet365 Stadium (if someone has missed it, Bet365 is a betting company), King Power Stadium (King Power Stadium is a travel retail group) and Vodafone Arena (Vodafone is a telecom company).

By Oscar Anderson

References:

The Ball is Round: A Global History of Football – David Goldblatt (2008)

www.fourfourtwo.com/features/brief-history-football-grounds

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sandygate_Road

https://spartacus-educational.com/Fstadiums.htm

https://www.news.com.au/sport/football/highbury-to-emirates-upton-park-to-london-stadium-how-premier-league-stadiums-have-changed/news-story/fd56bcb5fdb4726e26d8197113784109

https://www.connect4climate.org/infographics/evolution-eco-friendly-football-stadiums

Image sources:

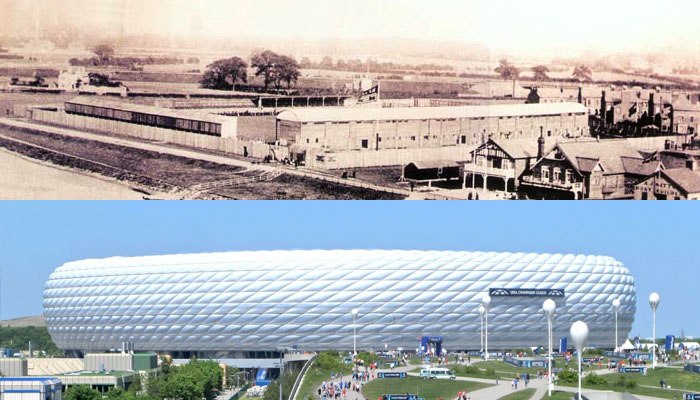

1.,2. (collage image ) unknown.

3. Thomas M. Hemy

4. Steve Daniels

5. Luicheto

6. Ngomoya

7. Nicholas Gemini